In a big win for Apple, a California district court dismissed sprawling claims that the tech giant collects data from its users even after certain privacy settings are disabled. While the ruling itself is a mixed bag, with some wins and losses for both sides, the Court’s focus on what a “reasonable expectation of privacy” is on the Internet ultimately meant Apple came out on top.

Background

This case concerns the collection and use of iPhone, iPad, and Apple Watch user data on Apple’s apps—including the App Store, Apple Music, Apple TV, Books, and Stocks. The 15 named Plaintiffs, including two minors, allege that Apple misled users into believing that certain settings would restrict Apple’s collection, storage, and use of private data, when in reality, the settings did no such thing.

In 2023, Plaintiffs filed a myriad of claims alleging, among other things, that Apple’s conduct violates California’s Invasion of Privacy Act (“CIPA”) and Pennsylvania’s Wiretapping and Electronic Surveillance Act (“WESCA”), breaches express and implied contracts, amounts to an invasion of privacy under the California Constitution, violates California’s Unfair Competition Law (“UCL”), and unjustly enriches Apple.

In Plaintiffs’ view, Apple has emphasized its commitment to consumer privacy through aggressive marketing strategies.

Examples of Apple’s billboards and advertisements cited in Plaintiffs’ Consolidated Class Action Complaint, ECF No. 115.

However, Plaintiffs alleged that Apple improperly collects and uses their data when they interact with its apps, in contradiction of these privacy promises.

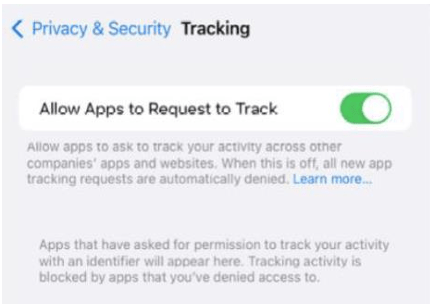

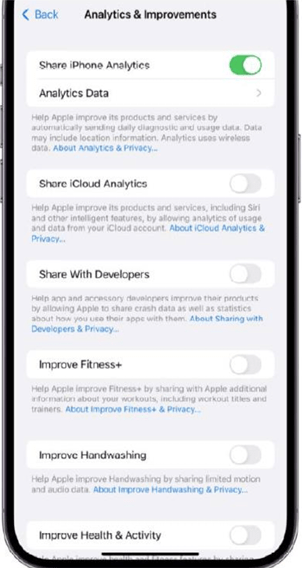

The allegations center on two settings governing the data collection at issue: the “Allow Apps to Request to Track” setting and the “Share [Device] Analytics” setting. Plaintiffs asserted that if these two settings were turned off, Apple promised that user data would not be collected.

In September last year, the Court had dismissed all of Plaintiffs’ claims as they related to the “Allow Apps to Request to Track” setting, noting that the setting clearly applied to “activity across other companies’ apps and websites” and not Apple’s tracking activity across its own apps and websites.

Additionally, by clicking on the “Learn more” link beneath the setting, users were presented with a disclosure titled “Tracking” which stated that “Apple requires app developers to ask for permission before they track your activity across apps or websites they don’t own in order to target advertising to you, measure your actions due to advertising, or to share your information with data brokers.” This statement also made clear that the setting would not apply to Apple’s tracking of users’ activity across its own apps.

By contrast, the “Share [Device] Analytics” setting allows a user to control whether to share certain data with Apple.

However, many of the “Share [Device] Analytics” claims were dismissed on other grounds, with leave to amend.

Subsequently, 10 of the Plaintiffs filed a First Amended Complaint (“FAC”) based only on the “Share [Device] Analytics” setting and adding a new claim under Cal. Penal Code § 638.51, the pen register provision of CIPA. Apple moved to dismiss.

CIPA § 638.51

First, Apple argued that Plaintiffs fail to identify a pen register. Section 638.51 defines “pen register” as capturing information “transmitted by an instrument or facility.” Cal. Penal Code § 638.50(b) (emphases added). As such, Apple contended that the pen register must be something separate from the instrument or facility that transmits the communications. Accordingly, its apps could not be pen registers, because the apps are themselves the source of the communications.

Plaintiffs argued, in their opposition brief, that it is the “processes within Apple’s Apps, not the applications as a whole, that operate as pen registers.” The Court took several issues with this argument. From a procedural standpoint, Plaintiffs’ allegations in their FAC and during oral arguments identified Apple’s apps as the recording devices or processes, not some undefined processes within those apps. Regardless, the Court still agreed with Apple that the statute’s definition of “pen register” necessarily applies only to a device or process separate from the source of the transmitted communications. If read the other way, the Court noted, the pen register statute would create criminal liability for call logs on cell phones because the logs list routing information like the phone numbers called from a particular phone.

“Plaintiffs’ argument that the alleged pen register is the processes running Apple’s apps as opposed to the apps themselves is a distinction without difference, because it does not change the fact that both are a part of the same ‘instrument or facility’ that is the source of the communication.” Order, at p. 5.

Plaintiffs also contended that other California courts have interpreted the term “pen register” broadly to include “processes that record users’ IP addressing information. . .” focusing “less on the form of the data collector and more on the result.” In these cases however, the alleged pen registers were third-party trackers that were embedded in websites and intercepted communications between the user and the website, so it was clear that the pen register was separate from the source of the communication. By contrast, Apple’s first-party apps and their underlying processes are a part of the source of the transmitted communications, which is enough to disqualify them from being pen registers. Accordingly, failure to identify a pen register under the statute’s definition is one ground for dismissing Plaintiffs’ Section 638.51 claim.

Next, Apple argued that Section 638.51 only regulates collection of telephone information and should not be extended to internet data. Apple noted that another provision in the statute requires any court order authorizing use of a pen register to “specify . . . [t]he number and, if known, physical location of the telephone line to which the pen register . . . is to be attached.” Cal Penal Code § 638.52(d)(3) (emphasis added). Extending Section 638.51 to internet communications would render this provision “nugatory.” The Court observed that recent decisions from California state courts have agreed, but federal district courts have largely rejected the argument that CIPA’s pen register definition applies only to telephone technology. While the Court characterized this as a “close call,” it was inclined to follow the majority rule in federal district courts and held that the pen register statute applies to internet communications.

Apple’s third argument in relation to the pen register claims was that the provision only applies to law enforcement and not private entities, citing Section 638.51 which prohibits the installation or use of a pen register, unless “a person . . . obtain[s] a court order obtained pursuant to Section 638.52 or 638.53,” and Section 638.52 and 638.53, which in turn, provide guidelines for “peace officers” or law enforcement officers seeking such an order. The Court disagreed, noting that the plain language of Section 638.51 suggests that it applies to the broader category of “persons” as opposed to only “peace officers.”

Lastly, Apple argued that Plaintiffs’ Section 638.51 claim fails because it contradicts their Section 632 claim. Plaintiffs’ Section 632 claim asserted that Apple’s apps recorded their “communications,” and Plaintiffs’ Section 638.51 claim asserted that the same apps recorded only the “dialing, routing, addressing, or signaling information.”

Plaintiffs’ first response to this was that there is no contradiction because certain processes within the app act as the pen register while others record the content of the communications. However, because Plaintiffs did not plead this process theory in the FAC, they were stuck with their allegation that it is Apple’s apps, not the processes therein, that record user data. Accordingly, Plaintiffs admitted that the apps “collect a variety of information – some of which are ‘communications’ and some which are ‘routing, addressing, or signaling information.’” The Court also rejected Plaintiffs’ attempt to salvage their claim by arguing that they that they pled their pen register claim as an alternative to their Section 632 claim, observing that in their pen register claim, Plaintiffs expressly incorporated by reference their allegation that Apple’s apps captured “confidential communications”. These inconsistent allegations and causes of action were another ground for dismissal of Plaintiffs’ pen register claim.

CIPA § 632

In the FAC, Plaintiffs reasserted their claim for violation of CIPA section 632, which prohibits “intentionally and without the consent of all parties to a confidential communication, us[ing] an electronic amplifying or recording device to eavesdrop upon or record the confidential communication.” Cal. Penal Code § 632(a).

Apple contended that Plaintiffs’ claim fails once again, because Plaintiffs do not plead that the data Apple allegedly collected was “confidential” or a “communication” or that Apple engaged in eavesdropping or recording.

First, Apple pointed out that California courts presume that internet communications do not give rise to a reasonable expectation of privacy. Apple explained that its apps operate using the client-server model, in which client devices request services from Apple’s servers that then record the request and transmit the requested information back to the client devices. Therefore, by their very nature, these transmissions are recorded on at least the recipient’s device.

Plaintiffs countered that their withdrawal of consent by turning off the “Share Device Analytics” setting created a reasonable expectation that none of their usage data would be sent to Apple. The Court disagreed, holding that while consumers may hold a subjective expectation that no usage data would be sent to Apple, that expectation is objectively unreasonable.

“No reasonable consumer would expect to engage in a transaction with Apple without some data being collected from Apple to process that transaction.” Order, at p. 10.

Plaintiffs’ focus on Apple’s collection of referral URLs and search terms did not change this result. The Court observed that, for Apple to respond appropriately to a user’s request, it must record the requested referral URL or search terms on its servers, and Plaintiffs failed to explain how such data collection is unnecessary. Accordingly, Plaintiffs did not sufficiently allege that any communication Apple collected was “confidential.”

The Court then turned to whether the data at issue was a “communication,” noting that under CIPA, “communication” refers to the substance or content of an exchange of ideas, not the “non-content-based conduct coincident to the communication.” The Court had previously dismissed Plaintiffs’ Section 632 claim holding that much of the information Apple allegedly collected—the kind of mobile device used, the device’s screen resolution, the device’s keyboard language, what users tapped on, which apps users searched for, and how long an app was viewed—was not communication. Upon amending the Complaint, Plaintiff added in categories of information they claimed satisfied the “communication” element, including URLs of referral websites that open Apple’s Apps, URLs from healthcare providers and financial institutions, users’ gender, user agent, IP data, referral app name, destination URL, search terms, and user actions.

As an initial matter, the Court rejected the contention that user agent, IP latitude, IP longitude, IP city, and user actions are “communication,” because they pertain to how, not what information is relayed. On the other hand, it acknowledged that search terms and URLs may constitute “communication” if the data convey the user’s inner thoughts and ideas. Here, however, the Court concluded that Plaintiffs’ searches for apps and stock symbols by name was more akin to browsing apps and stocks than exchanging a user’s substantive information. And although Plaintiffs alleged that Apple collected the URLs of referral and destination websites, they did not plead the specific text of those URL, so the Court was unable to infer that they contained users’ thoughts and ideas.

There was one notable exception in the Court’s reasoning—Plaintiff Carlina Green alleged that she used search terms such as “roommate,” “LSAT,” “screen time,” and “used cars,” which went beyond browsing specific apps on the App Store to reveal her inner thoughts and interests. Accordingly, the Court found that only Plaintiff Green alleged that Apple collected her “communication” under Section 632.

Moving onto the “eavesdropping or recording” requirement under Section 632, Apple did not dispute that its servers record user data but argued that Section 632 applies only to a person who “uses” a recording device and not to a company like Apple receiving data transmissions that are by nature recorded on servers. The Court rejected this argument due to lack of supporting case law and held that Plaintiffs sufficiently pled that Apple recorded their communication for purposes of Section 632.

However, Plaintiffs’ Section 632 claim was dismissed nonetheless because of their failure to demonstrate that the data Apple collects is “confidential.”

WESCA

Pennsylvania’s wiretapping statute, like CIPA, prohibits the intentional interception of the contents of any electronic communication using a device. 18 Pa. C.S. §§ 5702–03.

Apple argued that Plaintiffs failed to state a WESCA claim because they did not plead that Apple collected the “contents” of any communication, they failed to allege collection by a “device,” and Apple was the direct recipient of any communication.

Under WESCA, “contents” means “any information concerning the substance, purport, or meaning of that communication.” 18 Pa. C.S. § 5702. The sole Pennsylvania plaintiff in this case alleged that he searched for Zoom, Brave Browser, Instagram, and pdf scanner in the App Store and accessed other apps in the App Store through third-party websites. However, for the same reasons discussed above, the Court concluded that search terms do not constitute “contents” when the terms are simply the titles of particular apps on the App Store.

Turning next to “device,” which WESCA defines “any device or apparatus . . . that can be used to intercept a wire, electronic or oral communication,” the Court agreed with Apple’s argument that Plaintiffs’ mobile devices did not qualify, because the device performing the interception must be separate from the source of the communication. Plaintiffs thus failed to allege an intercepting “device” under WESCA.

Finally, Apple relied on the “direct-party exception” to argue that Plaintiffs’ WESCA claim could not proceed because Apple was the direct recipient of communication. The “direct-party exception” was previously abrogated by the Third Circuit in Popa v. Harriet Carter Gifts, Inc., 52 F.4th 121 (3d Cir. 2022), outside of narrow circumstances involving law enforcement. Despite Apple’s contention that the Popa holding was a non-binding “prediction,” the Court saw no reason from to divert from the Third Circuit’s reasoning that a broader direct-party exception would run contrary to another part of WESCA that allows only where all parties to the communication consent.

Despite rejecting Apple’s argument that the direct-party exception applies here, the Court dismissed Plaintiffs’ WESCA claim on other grounds detailed above.

California Constitution Invasion of Privacy

A claim for invasion of privacy under the California Constitution requires (1) a legally protected privacy interest, (2) a reasonable expectation of privacy, and (3) an intrusion that is “highly offensive” under social norms.

When previously dismissing Plaintiffs’ invasion of privacy claim, the Court had found that “no reasonable consumer would expect to engage in a transaction with Apple without some data being collected from Apple to process that transaction,” but stopped short of deciding exactly which data consumers should reasonably expect to be collected by Apple. Plaintiffs now argued that reasonable consumers would not expect Apple to collect data that is “unnecessary” for the functionality of its apps—the user’s gender, birth year, IP latitude, IP longitude, and URL— especially given that Plaintiffs withdrew consent to Apple’s collection of usage data by turning off the “Share Device Analytics” setting.

However, Plaintiffs did not clearly differentiate what data is “necessary,” and what is “unnecessary,” nor did they substantiate the premise that Apple’s apps do not require the “unnecessary” data elements to function—IP latitude and IP longitude are required by certain apps that provide location-specific services and date of birth is likewise necessary for apps providing age-restricted services. Further, Plaintiffs did not demonstrate that the data they deem “unnecessary” is highly sensitive—for example, consumers would only have a reasonable expectation of privacy in URLs that reveal information about their internet activity, but not in general URLs that do not reveal personal information, such as www.apple.com.

“Plaintiffs’ allegations concern data Apple allegedly collected from Plaintiffs’ interactions with Apple’s own apps. It is difficult to see how consumers would have a reasonable expectation of privacy in this context.” Order, at p. 18.

Having already rejected the contention that turning off the “Share Data Analytics” setting would create a reasonable expectation that Apple would not collect some user data, the Court dismissed the constitutional invasion of privacy claim.

California Unfair Competition Law

To have statutory standing to bring a UCL claim, Plaintiffs must allege they lost money or property as a result of Apple’s alleged unfair competition. Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 17204.

Here, Plaintiffs allegations that Apple “deprived Plaintiffs and Class Members of the economic value of their user data without providing proper consideration,” that they “seek damages for the price premium paid for their Apple mobile devices,” and that they “would not have purchased their devices from Apple or would have paid less for them” were found insufficient to establish standing to bring UCL claims.

Accordingly, this claim was dismissed as well.

Implied Contract and Unjust Enrichment

The Court had dismissed Plaintiffs’ original implied contract and unjust enrichment claims because they relied on the express contracts underlying Plaintiffs’ breach of contract claim. While a breach of contract and a quasi-contract can be pled in the alternative, the plaintiff must plead facts suggesting that the express contract may be unenforceable or invalid. Here, however, the FAC was devoid of any allegation that Plaintiffs’ express contract with Apple is unenforceable or invalid.

The Court therefore dismissed this claim.

While the Court expressed its doubt as to whether Plaintiffs can sufficiently plead their dismissed claims, it granted leave to amend “out of an abundance of caution.”

The case is In Re : Apple Data Privacy Litigation, No. 5:22-CV-07069, filed in the Northern District of California. We’ll be keeping an eye on this one!